Establishing a pattern for working with red eared sliders

In the spring of 2008 we found ourselves at the Concordia Turtle Farm in Wildsville, Louisiana.

Concordia is the largest turtle farm in the United States. It’s owned by the Evans family. They were very supportive of our goals and gave us access to a pond that had 5,000 red eared sliders (Trachemys scripta elegans) in it to use for our research.

They also gave us a shed to work in with power and water, and an ATV to move the animals between the pond and the shed.

In later years we became concerned that the reproductive physiology of all turtles was not the same. To deal with that problem the Evan’s family also gave us access to a spiny softshell turtle (Apolone spinifera) pond so we could test the new methods we were developing on a species that was very different from red eared sliders (RES).

The first challenge was to be uniform in our approach. For our results to be of any use we would need to treat every turtle the same. First we defined our goal as having every turtle lay all its eggs after the first induction. We called that “success.”

We quickly developed a routine. Every morning we’d collect 30-40 RES from the laying area. Because a lot of the turtles on the laying area were undertaking their normal migratory behavior (Parker 1984) they mixed with the turtles that had emerged to lay their eggs. There were often hundreds of RES on the laying area at a time .

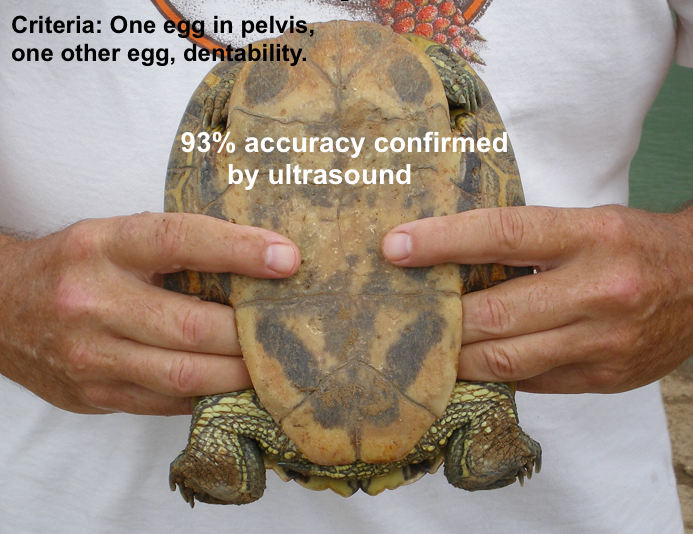

This dilution of laying females was a confounding factor that does not occur with wild animals that gather at their laying areas exclusively to nest. We tried to compensate for this confounding factor by selecting the animals to be induced by the following criteria: they had to have at least two palpable eggs, at least one of the eggs had to be in the pelvis, and the egg shells had to be firm enough not to dent when palpated lightly. The “correct” firmness would mean that they were fully calcified (Alkindi et al. 2006).

This test is highly subjective. Making the decision was the sole responsibility of just one individual so we could be as consistent as possible. The difficulty of judging egg firmness is highlighted by the fact that we occasionally induced females that ended up laying inadequately shelled eggs. Because of this confounding factor it would be unrealistic to expect a success rate on the turtle farm to be equal to inducing a wild population captured at their natural laying area.

This test is highly subjective. Making the decision was the sole responsibility of just one individual so we could be as consistent as possible. The difficulty of judging egg firmness is highlighted by the fact that we occasionally induced females that ended up laying inadequately shelled eggs. Because of this confounding factor it would be unrealistic to expect a success rate on the turtle farm to be equal to inducing a wild population captured at their natural laying area.

Using these criteria, each day we picked the first twenty animals that passed the test and those were brought back to the shed for induction each morning. The turtles were collected at the same time each morning. They were then washed and labeled before being placed in their laying containers.

Induction took place within four hours of collection and the turtles were then left undisturbed, with the containers covered, until the next morning. At that time the eggs were removed and the turtles released back into the pond. With the huge number of variables inherent in such a study we were careful to adhere to this pattern through all the years of our research with RES.