Red Eared Sliders Are Not A NZ Pest

In the past few years there’s been a lot of publicity about the potential for red-eared slider turtles to become invasive. Science is like any other field of human activity and it is subject to the fashions of the times. And the fashion today is that non-native species are a “no-no” and red-eared sliders are the “bad boys” of the turtle world.

But it is not that simple by a wide margin. Red-eared sliders are not super turtles; they cannot survive and reproduce anywhere. There are sharp temperature and moisture limits on the ability of their eggs to hatch and cool summer temperatures can limit the ability of adults to digest their vegetarian diet.

In the twentieth century red-eared sliders were sold by the millions to Buddhist countries for the express purpose of being released as part of their “life release” ceremonies. The release of millions of animals is going to upset the ecological balance for years; no matter what the animal’s ultimate fate is. For the most part these releases took place into severely disturbed eco-systems where the native turtles had been eliminated for many years so little real harm was done anyway. The issue of the impact on areas where there are native turtles has not been clarified either. Red-eared sliders co-exist with many other species of turtles in their native environments so it is not necessarily true they will have a negative effect on the local turtles in alien environments.

At the present time there is controversy about this issue in New Zealand, a country with cold summer temperatures and no native turtles. What follows below are a series of documents about the impact of red-eared sliders in New Zealand. They are arranged in increasing order of complexity with the most detailed material at the end.

——————————

An article written for a New Zealand Newspaper in 2014:

Well meaning but poorly informed councils have been trying to declare the red-eared slider turtle a pest here in NZ. This is a reaction to the fact that in selected areas around the world (Southern France, Japan, parts of SE Asia) these turtles have been able to survive. In Buddhist countries they have been released by the millions as part of Buddhist Life Ceremonies. It’s easy to see how that could cause problems. But New Zealand is vastly different from these countries and red-eared slider turtles are NOT a threat here. Here’s why:

Prior to importation of turtles being banned in 1965 about 30,000 red-eared slider turtles had been brought into the country. Since then about 2000 turtles have been bred per year in New Zealand. That’s a total of about 120,000 animals. If they were able to survive and reproduce in the wild there would now be many millions of them running around Northern NZ yet only a handful are found each year.

There are two reasons why they are not surviving. The first is that red-eared slider turtles cannot reproduce here without human help. Turtle eggs require high temperatures and lots of moisture to hatch. The few microclimates where it’s warm enough are usually too dry for the eggs to survive. There have been a few cases of turtle eggs hatching outdoors but they have always been situations near a north facing rock wall or other heat sink that was watered consistently. The sex of hatchling turtles is controlled by ground temperatures so even those situations are only able to produce males because of the cooler soil temperatures.

The other problem for turtles in New Zealand is that it is too cool in the summer and too warm in the winter. The cool temperatures in summer prevent them from being able to warm up enough to digest the vegetation they eat (they do NOT eat live fish, baby birds or eggs) and the relatively warm winter temperatures keep them from hibernating properly so they lose weight and die of starvation and disease after about four years on their own.

Turtles are also no threat to the few natural wetlands in Northern New Zealand because the water is too cool for them to be able to warm up enough to eat. Turtles might survive for a few years in warmer man made ponds, backwaters of the Waikato River and the numerous weed choked canals in the Hauraki Plains but, even there, they inevitably die after a few years unless they are fed protein based foods by people.

—————————

An article written as a submission to the Auckland Regional Council in 2018:

The following is a response to the suggestion that the sale of red-eared slider turtles should be banned in the Auckland area. This is only a brief summary of the facts about red-eared slider’s biology of relevance in New Zealand. We can provide details, references, original papers, and hard to get information from pre-internet days to verify what is written here. I would also be happy to come to Auckland and engage in meaningful discussion with all of the staff involved in this decision.

A. Where are all the turtles?

Red-eared sliders (RES) were imported into New Zealand from Louisiana, USA until 1965. A ban on importation was introduced in 1965 because the hatchlings were found to be carriers of several varieties of salmonella not previously known in NZ. However, by the time the ban was instituted, 30,000 animals had been imported and sold, so those alien species of salmonella were already widely distributed.

After the importation ban came into force, smuggling continued until the mid-1980s with 1000-2000 animals being imported per year. After that, back-yard breeders became common throughout New Zealand. After our first survey of NZ breeders in 1997, we concluded that about 2000 hatchlings were being sold per year and there was enough demand to sell another 300-500 animals at a retail price of $90.-$100. NZ each. At that time there were four main breeders and about twenty smaller ones.

Our second survey of breeders in 2005 came to similar conclusions. At that time the retail price varied from $70.-$100. NZ retail. Output was still about 2,000 animals per year, which seemed to be meeting market demand.

Our best estimate is that 1,000-1,500 RES are being produced per year now by back yard breeders. This output seems to be meeting or exceeding market demand.

Simple addition of these numbers means that at least 120,000 RES have been sold in NZ; most of those in the Auckland area. If they were capable of reproducing in the wild there would now be many millions in Auckland yet only a handful are discovered each year.

There are several reasons for this lack of turtles in the “wild”:

- RES turtles cannot reproduce here without human help.

RES eggs require high temperatures and moisture to hatch. The few areas where it’s barely warm enough (Far North) are usually too dry for the eggs to survive. There have been a few cases of turtle eggs hatching outdoors but they have always been situations near a north facing rock wall or other heat sink that was watered consistently. The sex of hatchling turtles is controlled by ground temperatures so even those rare situations are only able to produce males because of the cool summer temperatures in NZ.

Dr. Kikillus, in her 2010 doctoral thesis, used data-loggers to evaluate the temperatures of artificial turtle nests in 16 locations around Northern New Zealand. The only location that proved warm enough was next to a north facing boulder that would have served as a heat sink to keep the soil warm through the cool nights. Even that site would have only produced males. A similar but more primitive study I did in 1991 got identical results.

The majority of Dr. Kikillus’s thesis described in detail a variety of models designed to predict locations where various reptiles could reproduce. Some of her models predicted that red-eared sliders could reproduce in New Zealand. The models utilized a variety of air temperature measures but only included annual rainfall. These are two significant flaws since air temperature does not always reflect ground temperature and rainfall is heavy in the winter but usually sparse during the summers when red-eared slider eggs need moisture to hatch.

International studies have stated that females can hold active sperm for up to two years but by the end of the first year 80% or more of eggs are infertile. We have found that the fertility rate is much lower in NZ with turtles mated in the fall being sterile by the following spring.

2. The adult RES starve to death without supplemental feeding.

Hatchling RES are carnivores but as they age they become herbivorous because they cannot find enough animal based food to supply their increased body size. Active feeding requires water temperatures above 18-20o C and effective digestion of plant material requires hours of basking in full sun each day to produce core body temperatures in excess of 30o C. In NZ these requirements are only met for a few weeks a year.

Adult RES depend on the consumption of large amounts of vegetation. Live fish and birds are almost never part of their diet (but they do readily consume carrion). Favourite plants include oxygen weeds, water hyacinth and eel grass; all noxious weeds in New Zealand. In adults the natural diet by dry weight is 95-100% plant material.

Winter temperatures in the Far North of NZ (where RES are most likely to be able to reproduce) are too warm for effective hibernation so valuable energy is lost during the winter, compounding the lack of summer nutrition.

The only reason breeders are able to maintain RES in NZ is because they heat the water and/or feed them protein based foods like dog or cat chow, fish and beef heart. In captivity RES will refuse plant based foods except for a few weeks each year when their basking temperatures get high enough.

3. The RES die of disease.

RES that are released into the wild or escape are usually discovered in poor condition; emaciated, and with multiple lesions from ulcerative shell disease. Ulcerative shell disease is caused by infection with a variety of gram negative rods that gain entry to the living bone because of injuries to the outer keratin layer of the lower shell. The initial damage to the keratin is caused by metal road surfaces, concrete, and rocks along shore lines; all materials seldom found in their native habitat. In NZ’s cool climate the disease is chronically progressive and usually fatal within four years if not treated surgically. Like any chronic disease, ulcerative shell disease causes weight loss because of the extra energy consumed by the infectious process.

B. Other points:

COMMUNICABLE DISEASE:

In NZ many domestic mammals, 1% of people and almost all foul (chickens, ducks) are heavily contaminated by campylobacter, and to a lesser degree, salmonella.

Native NZ wild lizards are also known carriers of salmonella. Campylobacter is

ubiquitous in NZ; contaminating dogs, cats, the majority of farm animals, and waterways. Chickens and ducks are the most notorious source of both salmonella and campylobacter with contamination rates of up to 80%.

On a tour of turtle breeders in the North Island in 2005 I collected dirty pond water and infertile eggs from all their facilities. Unmodified pond water, pond water carried in selenite cystine broth for 3-7 days, and the yolks and shells of infertile turtle eggs from each breeder were all cultured onto xylose-lysine-deoxychoclate agar plates and incubated at 35o C. A minimum of six eggs was sampled from each breeder. The collected samples were cultured by the Whangarei Base Hospital Microbiology Department for salmonella and arizona. Campylobacter was incubated separately on other media from pond water and infertile egg samples. None of the cultures were positive for salmonella, arizona or campylobacter.

These results were surprising but were substantiated by Dr. Kikillus’s doctoral thesis in 2010 in which she found only 1.5% of 128 RES tested positive for salmonella (about the same carrier rate as for humans and less than for NZ native lizards). Her sample sites included pet shops and zoos where the RES were exposed to salmonella from other captive animals. I only tested turtle breeders.

The results we both obtained could be explained by the fact that conditions for back-yard breeders in New Zealand are much different than on commercial turtle farms in the USA. In NZ water is changed frequently, tanks are usually refilled with chlorinated tap water, offal from cattle and chickens are not used for food and the eggs are not sourced from contaminated soil.

SOCIAL FACTORS:

Banning the sale of RES is not a win-win scenerio. People will be hurt for no good reason. The retail value of red-eared sliders sold is about $140,000.00 per year. The retail value of durable goods and food sold for the ongoing care of these pets exceeds $1,000,000.00 per year. These business activities have been established in NZ for over fifty years. If there was a ban on the sale of turtles bred domestically compensation issues would probably arise.

People have always been attracted to turtles. They are the preferred pets for older, asthmatic children that cannot keep mammals. Turtles that survive to adulthood are often retained and passed down from generation to generation. Although some owners of adult animals do release them into dams, rivers and lakes because of their size, many owners of escaped adult animals often contact the SPCA looking for them.

Given the scientific facts, banning the sale of turtles is excessive, especially when compared to other pet species. We KNOW cats kill huge numbers of wild birds, can reproduce rapidly in the wild and carry disease. RES can do none of these things.

Can you imagine the fallout if the Council did the right thing and banned the breeding of cats? When debated in front of the press/public it would seem that the proposed ban on RES is nothing more than selecting a “soft target.” Given the lack of scientific evidence to justify such a ban it would not be a good look.

NEWS:

The publicity surrounding the finding of a RES in the “wild” around Auckland is an oxymoron when accompanied by dire warnings of a coming environmental disaster. If the turtles were that common then they would not be making the news.

THE LIST OF 100 MOST INVASIVE ANIMALS:

The Louisiana, USA, turtle farms had exported between 8-12 million animals annually for decades. In later years Korea imported up to 1.3 million per year, Italy about a million and Japan .6 million. Taiwan, South Africa, Israel, Australia, Thailand, Cambodia, and other European Union countries were also big importers. As of 2004 China had replaced Korea as the major importer. Red-ears have been able to reproduce in the “wild” in southern France and possibly Spain and Taiwan but not in northern France, central Italy or England.

Millions of these animals have been sold in Asia for Buddhist “Mercy Ceremonies” in which the turtle is marked and then released. So, it is no surprise that large numbers of red-ears have been found in waters already altered by human activities around the world. Even if they were incapable of reproduction, and could only survive a few years, the release of millions would have a significant local impact. This is how RES got on the ”100 most invasive” list

WHAT ENVIRONMENT ARE WE PROTECTING?

Natural cold water springs and bogs are now very rare in the Auckland area and much too cold for RES. Artificial ponds in parks and the back waters of the Waikato River are warmer but already heavily contaminated by alien species like mallard ducks, koi, goldfish, perch, Canadian geese, gambusia, tench, catfish and a host of water weeds; all of which have already dramatically altered any semblance of a natural NZ ecosystem. A RES turtle that might survive for 3-4 years in such an environment will have little or no additional impact.

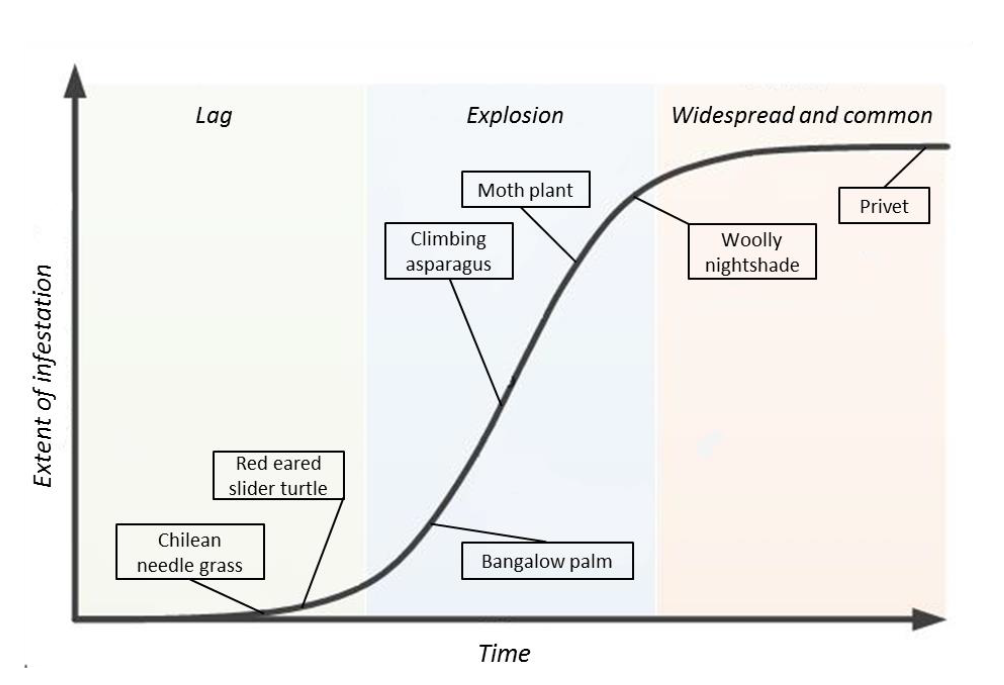

INACCURATE GRAPH:

This graph from page 23 of the Proposed Plan is NOT ACCURATE. RES have been imported or bred in NZ for 70 years. The projected logarithmic explosion has never occurred. This is just scare mongering; the sort of hyperbole that is not helpful.

This graph from page 23 of the Proposed Plan is NOT ACCURATE. RES have been imported or bred in NZ for 70 years. The projected logarithmic explosion has never occurred. This is just scare mongering; the sort of hyperbole that is not helpful.

————————-

An article published in the “Turtle and Tortoise Newsletter” in April, 2007:

The Red-eared Slider Turtle (Trachemys scripta elegans) in New Zealand

Mark L. Feldman

Box 285, Kerikeri, Northland, New Zealand, 0470; nz.feldman@yahoo.com

New Zealand (NZ) is unique in having no native turtles. Any turtles present in NZ have been imported as personal pets or via the pet trade before 1965. Over the past year there has been considerable misinformation about red-eared slider turtles (Trachemys scripta elegans) in the New Zealand media. The purpose of this presentation is to document the facts we do have about these turtles from overseas, and the research that has been done here.

History of the New Zealand market

Red ears were imported into New Zealand from Louisiana, USA until 1965. A ban on importation was introduced in 1965 because the hatchlings were found to be carriers of several varieties of salmonella not previously known in NZ. However, by the time the ban was instituted, 30,000 animals had been imported and sold, so those alien species of salmonella were already widely distributed.

The imported turtles came from turtle farms where they were raised in enormous concentrations (5,000-10,000 adults per surface acre). The animals were fed processed food but large amounts of salmonella rich offal and wild water plants from surrounding swamps were also consumed. These contaminated the stagnant water with a host of bacteria, including multiple salmonella serotypes. Waters in surrounding swamps were also contaminated with salmonella of similar varieties. Virtually all the hatchlings were carriers of salmonella (Chiodini and Sundberg, 1981). The salmonella was acquired as the eggs passed through the cloacae or were deposited in the contaminated soils at the farms.

After the importation ban came into force, smuggling continued until the mid-1980s with 1000-2000 animals being imported per year. After that, back-yard breeders became common throughout New Zealand. After my first survey of NZ breeders in 1997, I concluded that about 2000 hatchlings were being sold per year and there was enough demand to sell another 300-500 animals at a retail price of $90.-$100. NZ each. At that time there were four main breeders and about twenty smaller ones.

My survey of breeders in 2005 came to similar conclusions. The retail price varied from $70.-$100. Output was still about 2,000 animals per year, which seems to be meeting market demand.

The international situation and origin of the red-eared “problem”

The Louisiana, USA turtle farms have exported between 8-12 million animals annually for many years. In later years Korea imported up to 1.3 million per year, Italy about a million and Japan .6 million. Taiwan, South Africa, Israel, Australia, Thailand, Cambodia, and other European Union countries were also big importers. In 1997 the importation of red-ears was banned in the European Union. As of 2004 China had replaced Korea as the major importer. Red-ears have been able to reproduce in the “wild” in southern France (Cadi et al., 2004) and possibly Spain and Taiwan but not in northern France, central Italy (Luiselli et al., 1997), or England.

Millions of these animals are sold in Asia for Buddhist “Mercy Ceremonies” in which the turtle is marked and then released. So, it is no surprise that large numbers of red-ears have been found in waters already altered by human activities around the world. Even if they were incapable of reproduction, and could only survive a few years, the release of millions would have a significant local impact.

Biology

Active feeding requires water temperatures above 18-20o C (Ernst et al., 1994) and effective digestion of plant material requires hours of basking in full sun each day to produce core body temperatures around 30o C.

Adult red-ears prefer water 1-3 meters deep with copious amounts of vegetation. They pursue snails, insect larvae, crayfish, insects, worms, shrimp, tadpoles and other small creatures living around the margins of water plants. Live fish and birds are almost never part of their diet but they do readily consume carrion (Parmenter, 1980). In the process of hunting they consume large amounts of vegetation. Favourite plants include oxygen weeds, water hyacinth and eel grass; all noxious weeds in New Zealand. In adults the diet by dry weight is 95-100% plant material (Thornhill, 1982). They are known to move up to 9km overland between habitats.

Maximum longevity in natural situations is 30 years but most animals don’t live longer than 20 years. Only 1% of hatchlings survive to 20 years. Annual survivorship of adults is about 80%. Mated females can hold active sperm for up to two years but by the end of the first year 80% or more of eggs are infertile.

The lowest constant incubation temperature that produces hatchlings is 22.5o C but, at that temperature, most hatchlings are deformed or neurologically impaired (Ewert et al, 1991). To produce any females, eggs must experience constant temperatures above 28.3o C (Cadi et al., 2004). To produce all females the nest temperature must exceed 30.6o C for at least four hours a day during the middle third of development.

Successful nesting also requires soil that is moist enough to be suitable for nest building and maintenance of the water content of the eggs. Vermiculite with a water potential of -1500 kPa (.09 g water:1g vermiculite) is the driest condition in the lab that will allow the majority of eggs to escape fatal dehydration (Tucker et al., 2000).

Microbiology

Campylobacter and Salmonella are the most common causes of bacterial enteritis in New Zealand. About 1% of the human population are chronic salmonella carriers. Native NZ wild lizards are also known carriers of salmonella. Campylobacter is ubiquitous in NZ; contaminating dogs, cats, the vast majority of farm animals, and waterways. Chickens and ducks are the most notorious source of both salmonella and campylobacter with contamination rates of up to 80% (Alan, 2003). Campylobacter is by far the most important cause of human disease; out numbering reported salmonella infections by about ten to one in the North. The vast majority of cases go unreported.

On a tour of turtle breeders in the North Island in 2005 I collected dirty pond water and infertile eggs from all their facilities. Unmodified pond water, pond water carried in selenite cystine broth for 3-7 days, and the yolks and shells of infertile turtle eggs from each breeder were all cultured onto xylose-lysine-deoxychoclate agar plates and incubated at 35o C. A minimum of six eggs was sampled from each breeder. The collected samples were cultured by the Whangarei Base Hospital Microbiology Department for salmonella and arizona. Campylobacter was incubated separately on other media from pond water and infertile egg samples. None of the cultures were positive for salmonella, arizona or campylobacter.

These results were surprising. One possible source of error was carrying one set of pond water samples in selenite cystine broth for over 48 hours. Although an excellent selective media for salmonella, it is usually cultured onto plates after 24-48 hours. It’s possible the media proved to be toxic after that time. However, the untreated pond water should have held the salmonella alive for up to three months and the eggs were used as a back-up source; all proved to be culture negative.

The results could be explained by the fact that conditions for back-yard breeders in New Zealand are much different than on the commercial turtle farms in the USA. In NZ water is changed frequently, tanks are refilled with chlorinated tap water, offal from cattle are not used for food and the eggs are not sourced from contaminated soil.

Reproduction in New Zealand

There were two locations found where red-eared eggs were able to hatch outdoors in NZ. Each nest was situated next to a large, northwest facing heat sink (rock wall/concrete wall/ roofing metal) which warmed the soil through the night. Both also featured consistent artificial moisture; an unusual summer condition in most areas of NZ. I am also aware of turtle nests hatching successfully in glass houses that were watered frequently.

Except for the above examples, all breeders that discovered eggs outdoors more than two week after oviposition, found they were dead.

During the summer of 1991, I constructed an artificial nest in Mangonui (Feldman, 1992) in the Far North, one of the warmest areas in NZ. The nest was in an ideal location to capture the heat of the sun, facing due north on a 30 degree slope with no nearby shade. The mean low-high temperatures within the nest for January were 21o C – 23o C and for February were 20 – 24o C. The air temperature for that summer averaged .8o C below normal. At those temperatures even the most cold adapted of Canadian turtles could not breed here (Bobyn, 1991) but there were no eggs in my artificial nest. The presence of metabolically active eggs can raise the nest temperature by 2-7o C in the last third of incubation (Burger, 1976), but this is too late to influence sexual determination.

Results of a turtle hunt in NZ

Once you know how, it is very easy to detect adult turtles and their nesting sites. During the summers of 1993 and 1994, during the height of the nesting season, I traveled throughout the upper North Island looking for turtles. I only investigated a few ponds in towns and cities because I assumed that there would inevitably be some escaped or released pets there. I focused on “wilder” areas looking for breeding populations in warm water habitats created by human activity. The most likely environment for them that I detected was the numerous weed choked canals in the Hauraki Plains. In these areas the water was relatively warm and there was an abundance of water plants to eat. I found no turtles and no evidence of nesting.

During 21 years of living in the Far North I have trapped or received several adult female turtles that had found their way into area streams or neighborhoods. All were emaciated and had significant ulcerative shell disease. Clarice Ford, who receives and redistributes unwanted turtles in Auckland, told me that almost all of her turtles (30 per year), arrive in similar condition. Turtles deposited in the moats at the Auckland Zoo also prove to be frequently infected.

The fate of pet turtles in NZ

The vast majority of hatchlings sold in the pet trade die before one year of age. Estimates from oversea suggest survival is 5%. Survival might be higher here because the animals are much more expensive; prompting people to take better care of them. Contrary to folklore, turtles are quite delicate and require large amounts of calcium, unfiltered sunlight or vitamin D supplements, lots of vitamin A or fresh vegetation, and an environment with no hard, rough surfaces in order to survive for long periods.

If the average turtle is eight years old when it is freed or escapes it can be expected to live for another twelve years under ideal circumstances. But turtles that are released into the wild or escape are usually discovered in poor condition; emaciated, and with multiple lesions from ulcerative shell disease.

Ulcerative shell disease is caused by infection with a variety of gram negative rods that gain entry to the living bone because of injuries to the outer keratin layer of the shell. It’s usually chronically progressive and ultimately fatal if not treated surgically (Feldman, 1998). The origin of the injuries to the keratin are the concrete ponds the turtles are often kept in and the sharp edged rocks found in many situations in NZ, but uncommon in their native environment. Like any chronic disease, ulcerative shell disease causes weight loss because of the extra energy consumed by the infectious process.

I suspect that the other reason “wild” red-ears are always emaciated here is because of the low water and air temperatures in NZ. The low water temperatures inhibit feeding and the low air temperature makes it difficult to digest the plant material they depend on for nourishment.

Financial and social factors

The retail value of red-eared sliders sold is about $170,000. per year. The retail value of durable goods and food sold for the ongoing care of these pets exceeds $1,200,000. per year. These business activities have been established in NZ for over fifty years. If there was a ban on the sale of turtles bred domestically compensation issues would probably arise.

People have always been attracted to turtles. Demand in NZ has always exceeded supply. They are one of the preferred pets for older, asthmatic children that cannot keep mammals. Turtles that survive to adulthood are often retained and passed down from generation to generation. Although some owners of adult animals do release them into dams, rivers and lakes because of their size, many owners of escaped adult animals often contact the SPCA looking for them.

Conclusions

Except in exceptional circumstances, there is good evidence that red-eared sliders cannot reproduce in NZ successfully because of the consistently low temperatures and sparse summer rainfall in most of the country. There is some evidence that they cannot survive for more than a few years in the “wild” despite the ample supply of invasive water plants available for food. The fact that it makes the news when one is caught supports this view.

However, they might be able to survive longer in parks, artificial ponds and waterways already heavily impacted by man, especially if fed by visitors. If native invertebrates exist in these altered environments it is possible that red-eared slider turtles could have an effect on their populations. Given their long history in New Zealand I suspect they would already be a problem if they were ever going to be.

References

Alan, B. (2003). Crook chooks. Consumer. 431: 12-13.

Bobyn, M. (1991). Personal communication from Department of Zoology, Guelph, Ontario, Canada.

Burger, J. (1976). Temperature relationships in nests of the northern diamondback terrapin, Malaclemys terrapin terrapin. Herpetologica 32: 412-418.

Cadi, A.; Delmas, V; Prevot-Julliard, A; Joly, P; Pieau, C; Girondot, M. (2004). Successful reproduction of the introduced slider turtle (Trachemys scripta elegans) in the South of France. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 14: 237-246.

Chiodini, R.J.; Sundberg, J.P. (1981). Salmonellosis in reptiles: a review. American Journal of Epidemiology 113 (5): 494-499.

Ernst, C.H.; Lovich, J.E.; Barbour, R.W. (1994). Turtles of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D.C., USA.

Ewert, M.A.; Nelson, C.E. (1991). Sex determination in turtles: diverse patterns and some possible adaptive values. Copeia (1): 50-69.

Feldman, M. (1992). Can turtles reproduce in New Zealand? Moko, winter issue: 14-16.

Feldman, M. (1998) The ulcerative shell disease in New Zealand turtles. Moko, summer issue: 11-13.

Luiselli,L.; Capula, M.; Capizzi, D.; Filippi, E.; Jesus, V.; Anibaldi, C. (1997). Problems for conservation of pond turtles (Emys orbicularis) in central Italy: is the introduced red-eared turtle (Trachemys scripta) a serious threat? Chelonian Conservation and Biology 2(3) 417-419.

Parmenter, R. (1980). Effects of food availability and water temperature on the feeding ecology of pond sliders (Chrysemys s. scripta). Copeia 1980(3): 503-514.

Thornhill, G.M. (1982). Comparative reproduction of the turtle, Chrysemys scripta elegans, in heated and natural lakes. Journal of Herpetology 16 (4): 347-353.

Tucker, J.K.; Paukstis, G.L. (2000). Hatching success of turtle eggs exposed to dry incubation environment. Journal of Herpetology 34 (4): 529-534.